By Terris Harned (NWOrpheus)

I feel incredibly fortunate to be a gamer in 2019. I’ve been a gamer since I was a toddler in diapers. My parents’ neighbors had an arcade Asteroids machine that I was allowed to play with (poorly) whenever we went over to visit. My recollections of this time aren’t great, of course, but I remember two things distinctly: a yellow plastic semi-truck with a red seat that I used to ride all over the place, and that Asteroids arcade game.

Later, I had an Atari 2600 with an Asteroids cartridge, along with Missile Command, Combat, and eventually Pitfall! After that, I played on the NES, the Sega Genesis, and the Super NES. Eventually, my mom got a workstation computer from her employers, which had Tetris. That computer got upgraded to a 386 with Windows 3.0 and MS-DOS 5.1, on which my favorite games were the Pools of Radiance and Champions of Krynn games that I had on 5.25-inch floppy disks, complete with the little wheel you had to turn (an early form of DRM).

Suffice to say, I’ve watched the gaming landscape evolve over the last 35 years, and 2019 is a great time to be a gamer. We’re living in an era with a massive array of gaming options, from mobile phones smaller than my old floppy drives that can store dozens of games, to Virtual Reality headsets like the Oculus Rift in my living room. Think about that for a second. From the Atari 2600 to Virtual Reality, in 35 years? The pace of technological advancement is truly amazing, and few industries have seen it advance as rapidly as gaming.

Which is why I feel that it’s beyond time we evolve the terminology we use to describe video games and the studios that develop them. At this point in time, there are only two widely used designations for such studios: AAA (or Triple-A) and Indie, short for independent. In order to understand why we need better definitions, let me first define these two terms.

AAA vs Indie Definitions

AAA studios are typically defined as having large teams of developers; “usually with hundreds of employees,” as Raka Mahesa defines in a 2017 article. Ubisoft, one of the largest AAA studios, employed 13,742 persons as of March 31, 2018. The games they produce have budgets in the multi-million range. In 2012, according to William Usher of Cinemablend.com, the low end was $20 million. Rockstar Game’s infamous Grand Theft Auto V allegedly cost around $265 million to produce, as reported by The Scotsman.

Sadly, that is the most basic definition of a Triple-A studio: massive budget and huge development team. In a more general sense, they are also expected to produce higher quality games, especially in regard to graphics realism and sound production. AAA games have also been likened to “Summer Blockbuster” titles in the movie industry, with other games being compared to Indie Films, or perhaps vulgarly as “B titles,” in comparison to movies popularized by their low production values (ala Ed Woods’ Plan 9 from Outer Space).

Independent studios are, in contrast, defined merely by their choice to self-publish. A more expansive definition might limit the number of employees to 30 or less, as suggested by Raka Mahesa. The widely popular Stardew Valley, for example, was made by single-handedly by Eric “ConcernedApe” Barone, with minor publishing support from Chucklefish, the small studio behind Starbound and Wargroove. Stardew Valley was produced on a hand-to-mouth budget and has sold over 3.5 million copies. Supergiant Games, creators of acclaimed titles Bastion, Transistor, Pyre, and their current work in progress Hades, operates on a studio of just 16.

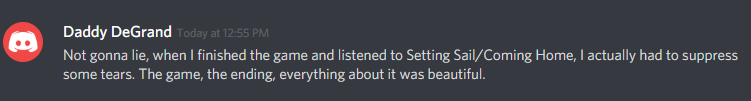

Daddy DeGrand from the Supergiant Discord, talking about the game Bastion. Check out his playthrough of Bastion on YouTube.

Indie games are also often known for having more stylized or cartoony visuals, with some even being known for a distinct feel. Indie studio Klei, for example, has created titles including Oxygen Not Included and Don’t Starve, and while the two graphic styles are distinct from each other, there are also similarities between the two both visually and in audio composition.

Perception

Aside from the core definition of Indie vs AAA titles, there are certain perceptions about the two studios, though these have shifted greatly in the last two decades. In fact, the term AAA studio originated in the late ‘90s at video game trade shows, such as E3, CGDC (Now GDC), and CES, as cited in the book High Score!: The Illustrated History of Electronic Games by Rusel DeMaria and Johnny Lee Wilson (2002).

Major developers at the time felt a growing need to differentiate themselves from smaller studios, which at the time typically published shovelware: mass-produced games of the early ‘90s after the introduction of the CD-ROM. These were sometimes collections of previously published titles where publishers would shovel in as many titles as they could because of the expansive storage volume of the CD-ROMs in comparison to their 3.5-inch floppy disc predecessors.

We can actually see a similarity to the shovelware issues of the ‘90s with the opening of Steam’s virtual store platform to anyone who wishes to post a game. In fact, a large impetus for me writing this article was was my infuriation that the artistic masterminds at studios like Klei and Supergiant were being categorized with such abominations as Toilet Simulator or George VS Bonnie PP Wars. Yes, both of those are actual games; no, you shouldn’t click on the links.

Throughout the 2000s and early 2010s, there was a strong belief that AAA titles were, by default, of higher quality and worth. Many AAA developers, such as Matt Firor of Mythic Entertainment and Todd Howard of Bethesda, posited that “a so-called AAA game is one with an appeal broader than the typical ‘hardcore’ demographic,” according to a 2005 E3 panel hosted by Carly Staehlin, the former producer of Ultima Online. Indie games, conversely, were all niche market games with a small audience.

This perception was overthrown with the arrival of titles such as Mojang’s Minecraft, Re-Logic’s Terraria, Team Meat’s Super Meat Boy, and Supergiant Games’ massively acclaimed Bastion. This is just a tiny list of games with extremely humble beginnings who still have huge followings and have launched successful development careers for Indie developers. The so-called Indie renaissance has continued through the last two years with titles like Hollow Knight, Dead Cells, and What Remains of Edith Finch, which won Best Narrative at the Game Awards in 2017.

Now, we’re seeing more and more that AAA studios are unwilling to take risks. With production values in the hundreds of millions of dollars, this is somewhat understandable. The end result is Ubisoft’s showcase at E3 2019 that might as well have been called “Tom Clancy’s Paycheck”. Every year we see a new Call of Duty title from EA, it seems, as well as repeat offenders like FIFA or NBA Live games, with token adjustments from the previous year’s offering.

People are becoming increasingly wary of developers like Bethesda, whose myriad antics around Fallout 76 have been nothing short of legendary. Meanwhile, we can anticipate at least another two years of waiting before we see Starfield, which will be Bethesda’s first truly new IP since the death of their IHRA Drag Racing series in 2006.

In short, innovation and art seem to be dying out in the AAA game industry, while some of the more successful Indie studios, sometimes referred to as Triple-I (because III just looks like 3), continue to make waves in the industry.

Structure

One of the true core differences between Indie and AAA studios is the structure under which they work. As no two studios are exactly the same, there will be some generalizations to follow, but by and large they’re applicable.

In 2017, Jeff Grubb of Venturebeat.com wrote that “the director is the top of the film-making pyramid, but in [AAA] game development, that’s the CEO.” What I take Grubb to mean here is that in film, which even on the blockbuster level is generally considered an art form, the director, who is a creative entity with a creative vision, makes the decisions on the direction of the project. A CEO, typically, isn’t someone concerned with art but is rather beholden to the shareholders of a corporation. Specifically, the CEO’s primary job is to make the shareholders money.

Because of this, AAA game development’s primary focus is profits. That’s not to say that there’s no intrinsic art value to AAA games. It does mean that when a choice is made between what will create the greatest emotional impact versus what will bring in the greatest profit, in AAA games the choice will be profit. This is why so many AAA developers, according to Grubb, are leaving AAA studios to create their own companies. Interestingly enough, even after creating those companies, many of these developers choose to take directorial positions rather than that of the CEO.

A great example of this is the famed director, designer, writer, and producer, Hideo Kojima. After his unpleasant departure from Konami, after a career there lasting three decades, Kojima re-opened his private studio Kojima Productions. Kojima, who is most well known for the lucrative Metal Gear Solid franchise, has a resume that would have landed him almost anywhere he wanted to go. That ended up being a place where he could take risks on an artistic vision, namely Death Stranding, a title that has the industry on the edge of its seat. At San Diego Comic-Con 2019, Kojima was quoted as saying (through a translator): “I want to create something that gives more inspiration to the world.”

Developers at AAA studios are also often expected to work under egregious conditions, typically called “crunch”. The idea behind crunch was originally a final push to meet a deadline. Unlike games in the early ‘90s and late 2000s, deadlines are much harder to push back, largely due to pre-orders. Instead, developers are expected to sacrifice their personal lives and work in excess of 60 hours per week, often for months at a time.

Despite this being a recent hot topic issue, it’s sadly nothing new, as demonstrated by the EA Spouse Controversy of 2004. Polish development studio CD Projekt Red, best known for Witcher 3 and the upcoming Cyberpunk 2077, has come under fire recently for long term crunch practices as well, and so the practice seems unlikely to dwindle any time soon.

Former president of Epic Games, Mike Capps, once stated that Epic Games would not hire people willing to work for less than 60 hours per week, according to an article by Ian Williams (Jacobin, 2013). This while sitting on the board of the International Game Developers Association, a non-profit group comprised of video game industry employees, ostensibly dedicated to “improve their lives and their craft.”

“Labor Creates Games” is a motto taken up by many against crunch, including the Game Workers Unite organization.

Everything isn’t always gravy and roses for Indie studios, granted. They’re not immune to crunch, though my perception is that it’s much less frequent, more self-imposed, and more a labor of love, rather than a “voluntary” effort that is anything but.

Frequently smaller studios are forced to turn to crowdsourcing for funds, lacking the financing granted by a large publisher. Others turn to Early Access, which gained popularity on Steam, and now also exists on the Epic Game Store. There are pros and cons to these approaches, however; they can only carry a game so far, and a failure to meet schedules could result in an unprofitable venture. Large numbers of abandonware stand testament to this, and also contribute to a modern reluctance for gamers to approach Early Access titles, seeing them as unwise investments.

On the other hand, smaller studios can do what game development studios are meant to do: They can make games. Many sources report an increase of creative freedom while working with smaller studios, and in Grubb’s article mentioned earlier, Jonathan Blow of Thekla, which created The Witness, is quoted as saying “Me going to direct Assassin’s Creed would not be a step up for me. It would be a step down. It would represent a loss of freedom in what I choose to do and a decreased quality of life.”

Conclusion

It is my strong belief that the term AAA is no longer an indicator of quality. Neither, for that matter, is Indie. Both types of studios that fall under those categories have been shown to make games that are critically acclaimed or lack redeeming qualities.

True, there are more AAA titles that utilize realistic graphics or, as a recent trend, stop motion animation. AAA studios are also more likely to be able to afford to hire famous actors like Kevin Spacey or Jon Bernthal. On the other hand, Quantic Dream is a relatively small studio, with a mere 180 employees, and yet they hired Ellen Page, Willem Dafoe, and Eric Winter for Beyond: Two Souls and have made a name for themselves using motion capture. Their five published games are known for being artistically focused, with strong and engaging narratives.

The line has blurred greatly between AAA and Indie studios, and I don’t think that quality should be the determining factor between them anymore. Neither should budget. I think instead we should consider: Is a game’s development focused primarily on profit or on creativity? Is the developer making a title to please gamers, or to please their shareholders?

I’d definitely like to bring the term “shovelware” back into play, mostly used to describe the dregs I have to wade through on Steam. As for the other studios, I really don’t know what to call them. When I think of developers like Ubisoft or publishers like EA, all I can think of is my time as a bookseller, dealing with “Mass Market” paperbacks. Maybe “Mass Market” and “Niche” would be the better terms? I definitely dislike any sort of letter grading type system, I know that much.

What do you think, reader? Is there a better set of terminology we could use to describe gaming studios? Or should we just stop trying to label the game based on who makes it, and just focus on what’s important: Is the game fun, or not? Head on over to the OnRPG/MMOHuts Forums and share your thoughts!